Late Night waitress (who said she’d do “almosty anything

to get out of this town”),) Clovis, New Mexico. 2010

by Bruce Berman

I hope she did (without the “anything),”

Late Night waitress (who said she’d do “almosty anything

to get out of this town”),) Clovis, New Mexico. 2010

by Bruce Berman

I hope she did (without the “anything),”

Akron, Ohio, 1970 by Bruce Berman

Photograph and Text by Bruce Berman

This was shot a long time ago. 55 years, in fact.*

Do things get better with age and time?

I look at this image and think, “… if I was grading this, if this was one of my students’ work, well, why didn’t you use HDR while shooting and in Post Production, get rid of the fuzzy glowing lights? Why didn’t you straighten out the verticals, in PhotoShop so it’s “architecturally correct’?”

And, of course, this would be completely missing the soul of the image! The charm is the ‘flaws.’ The charm is the youth that’s unaware of what the flaws are, or that there are such aa thing as ‘flaws.’

First of all, this was shot on 2 1/4″ film. There was no PhotoShop and no way in a darkroom to do anything about “verticals.” I had no idea, 55 years ago about any of that. AND, if I had, I’d have told you to go jump in the lake (Lake Michigan. If it was now, living where I live, I’d suggest you jump in the desert).

“I dig it the way it is and… so what!”

So, have I become a hypocrite?

Hmmmmmm… maybe.

Or maybe I just shouldn’t be teaching at all and just concentrate on my own evolution.

Maybe instead of picking away at these little “legalisms,” I should be worrying about what I’m doing now and what I’ll be doing in the next 55 years (!).

Instead of asking one –or myself– to do all these little tricks that are so easy in the Digital Age, I should be asking, “Do YOU dig it?”

That’s all that really matters, me thinks.

*BTW, while shooting this, someone –probably a bank guard– called the police, who arrived within minutes.They wanted to know what I was doing. I was a long-haired dude scoping out a bank in Akron. Of course they wanted to know what I was doing.

I just explained I was attracted to the night scene and the architcture was neat and that I was just an amateur (which I almost was).

On his CB he called into the dispatcher and dismissed the situation by reporting, “There’s no problem… we just have a shutter bug on our hands.”

Loved that!

Pinhole #91, El Paso, Texas

Text and Photograph by Bruce Berman

Remember these?

2 1/4″ film developing reels.

How many million times did I load these with Plus X film after a shoot.

How many hundreds of times did I ruin a few frames because the film end stuck to the layer below?

Guilty!

After “it was all over,” the film era that is, I used pinhole to demonstrate the fundamentals of photography to several generations of students. A lot of the old gear made good subjects. The old was useful to the new. Made sense. Like a circle completed.

They loved it. I loved that they loved it.

Like a morning mist those times were gone in a flash.

That’s one of the reasons we do photography, right? To hold onto what is gone.

Yeah!

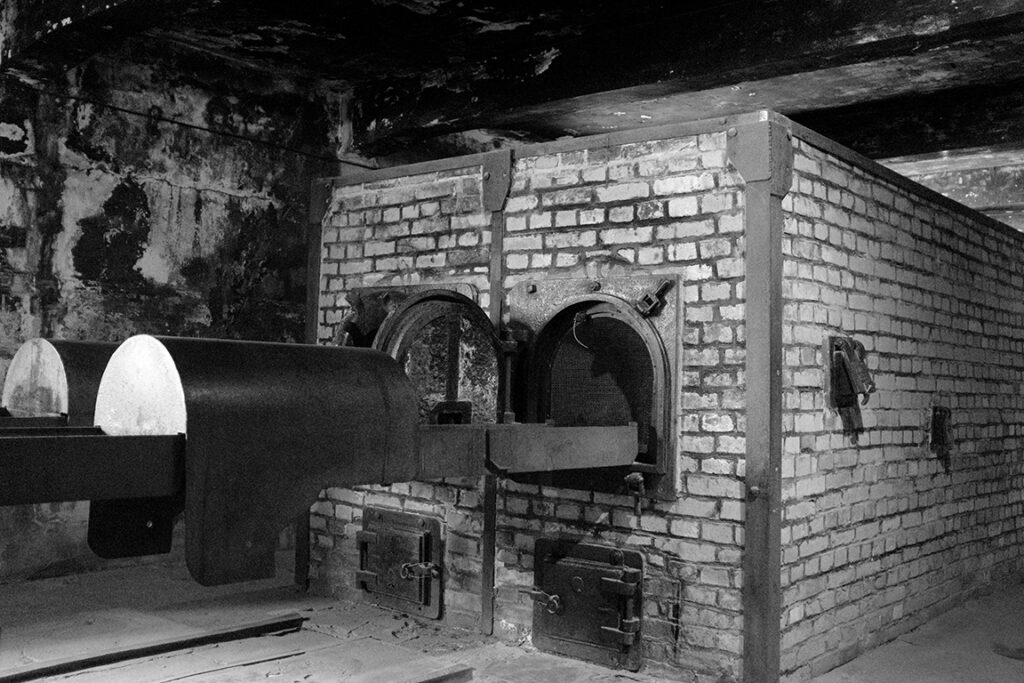

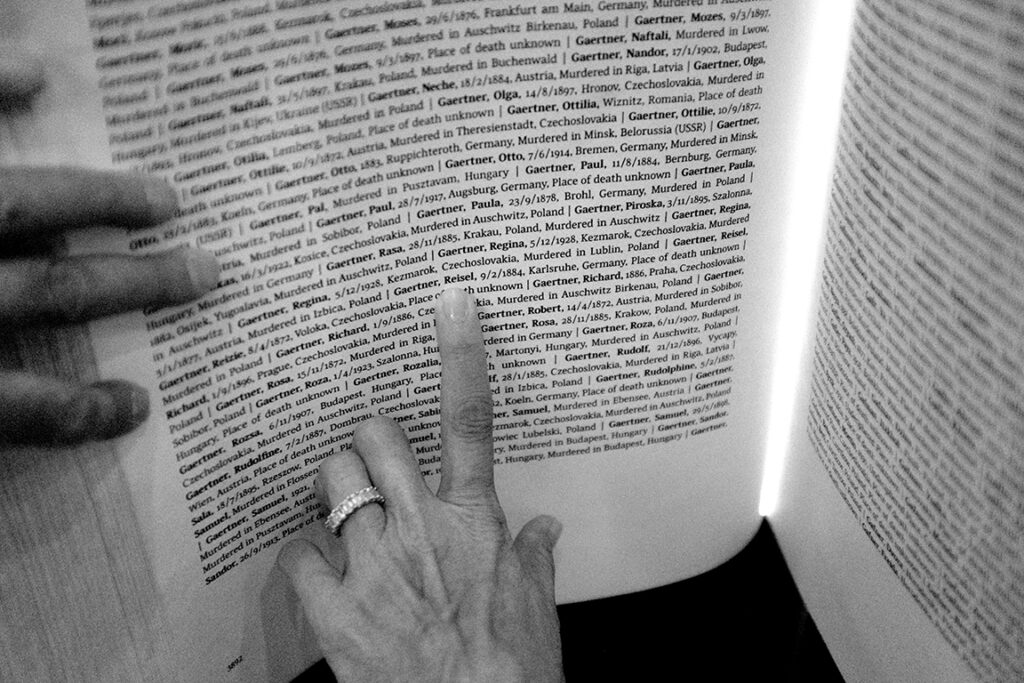

Editor’s Note: Walter Chayes is a photographer, financial consultant, a bicyclist and a humanitarian. He –and his brother– started in photography in their teens in New York City. Walter’s work is known for capturing important moments and for its strong graphic content. In this body of work, a work of the heart, Walter visits the epicenter of the Holocaust and, in essence, visits the scene of his Grandparents’ last days. This is difficult work to do. It was difficult work to edit. The message of the work is, “Never Forget/Never Again.”

Bruce Berman, Editor

DocumentaryShooters.com

Text and Photographs by Walter Chayes

Despite being an American-born Jew whose parents narrowly escaped the Holocaust, there was always a certain remoteness, an intangibility, when I read of the horrors of the concentration camps. How could a (lower) middle-class New Yorker, educated in the 20th Century identify with the thought of gassing 20,000 human beings, men, women and children in a single week…wiping out six million innocent people in the German’s attempt to eradicate Judaism? How could I feel the horrors that my grandparents felt as they were led into the gas chambers of Auschwitz?

As an early member, and past President of the El Paso Holocaust Museum, I jumped on the opportunity to join a Poland-Israel trip jointly organized by our Museum and the local synagogues in June of this year. In preparation for my trip I read many books on the history of the Holocaust, Eli Wiesel, Viktor Frankl and Primo Levy were among the most eloquent historians that told of their suffering. But I also read more objective historical books on the Holocaust…the history leading up to the horrific events, the ease with which dormant anti-semitism became a dominant force in German life. I also read psychological analyses of the victims…why didn’t they leave when they had the chance, why didn’t they fight back when faced with certain death, and so on.

Right there, right in La Mesa, New Mexico, four days ago, is the lesson on why we do DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY!

My documentary photography class at New Mexico State University (NMSU) has been doing a project for the past twelve years, the Small Village New Mexico project (SVNM), documenting the small villages in southern New Mexico.

One of the students’ favorites towns is La Mesa. Probably because there has been one guy, Joe Mees, who rebuilds cars and Harleys, and has always been very welcoming to the students. It doesn’t hurt that he looks very cool!

Last Thursday, we met Tim Mees, Joe’s son.. He told us of that “Joe has been bed-ridden for about a year.”

Bud Love is from my new book -BACKLAND- now available on Amazon. It’s a book about wandering in the 1975-2000 era.

https://amzn.to/3K6SwVT

Stay tuned.

The Small Village New Mexico project (SVNM) was created as a Documentary Photography teaching tool, for my advanced photojournalism class at New Mexico State University.

Article by Bruce Berman

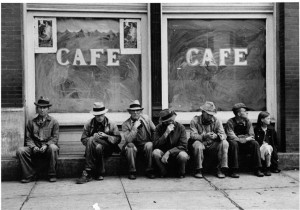

The Atlantic Monthly just published an article about the FSA (Farm Security Administration) and how minority Americans (African-Americans and Latino Americans) were ignored by the FSA during its four year run.

It’s title is: Whitewashing the Great Depression.

It is factually misinforming.

Four years ago I co-authored (with my colleague Dr. Mary Lamonica) an article titled, “The Photographer as Cultural Outsider.”

It focused on Russell Lee and his 1949 project shot for George I. Sanchez who was the first Latino Dept. Head at UT-Austin and one of the early Civil Rights warriors in LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens). Sanchez had created The Study of the Spanish-Speaking People of Texas project. Lee, of course, was an FSA shooter of great renown and prestige (and later OWI/Office of War Information). He had settled after his WW 2 service in Austin, Texas, the same city as Sanchez’.

Our article was a little more nuanced than the Atlantic piece and delved into the issue of cultural identity of the photographer (or writer or filmmaker) in shaping not only his/her viewpoint but how various ethnic subjects react to a photographer.

Text by Bruce Berman

Photograph by Stephen Wilkes

My father, Irving “Punch” Berman was born on Ellis Island in 1906. It was the day his parents -my grandparents- arrived in America. He was the first American in our family.

He was grateful to be here.

The documentation of “The Island” by Stephen Wilkes is documentary photography at its best: it preserves our memories and it stimulates inquiry.

See Stephen’s work: https://stephenwilkes.com/fine-art/ellis-island/

Was this the exact room he was born in? Who knows?

Was this the exact clinic? Yes.

Was he an accidental American? Most definitely.

The mystery in our family was, always, twofold: a) why did they let them in? My grandfather, Jacob, was dead within 6 months, of Tuberculosis. He never made it out of the lower east side. He was that sick it must have shown as the entry guards were interviewing. His mother, my grandmother Anna, died of the same illness seven years later (in Denver). The immigration authorities usually sent the sick ones back on the boat as it turned around and went back to England or Lisbon or wherever. It normally would have been a long sail back to Odessa (which they were escaping from, from the Cossacks), or wherever they could afford to be. And, c) When did he become a Berman. For that matter when did he become Irving? I know how he became Punch because he told me so. That will have to wait for another post (tease tease).

My niece Isabel, has tracked down the family history and it turns out his name was Isidor Yonofsky.

Some secrets, I guess, are lost to the fogs of time.

Note: Much thanks Stephen Wilkes.

John Vachon, Chicago, 1940

Washington, D.C., circa 1920. “People’s Drug Store, 7th and M.” Your headquarters

for Bed Bug Killer, Corn Paint (“for Hard and Soft”) and the ever-popular Rubber Goods.

National Photo Company via Shorpy

July 1942. “Chevy Chase, Maryland. Serving supper to motorists at an A&W Hot Shoppes restaurant

on Wisconsin Avenue, just over the District line,” by Marjory Collins for the Office of War Information

Read More: https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/womphotoj/collinsessay.html

School Girls on a bus in Juárez, 2002

How many times have I wanted to cross over the Bridge to Juárez, jump on a ruta autobus and never return to mi lado (the other side, El Paso, America) again?

A bunch of times. Actually, in the last decade, every time. ¡Muchos tiempos!

When I go to Juárez I realize within minutes that the bubble I live in America is a prison not a home. It’s a construction. A development.

Instead of working this feeling out, I take photographs, like an archeologist, always trying to root out what this means, and, for a very long time that has been enough.

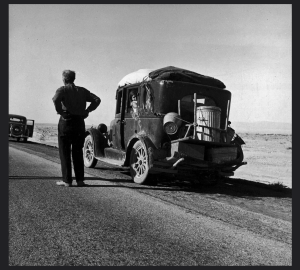

Photograph: Dust Bowl gear, 1930s, by Margaret Bourke-White

Photograph: Dust Bowl gear, 1930s, by Margaret Bourke-White

High School Beach, Venice, California, 1949 by Max Yavno

Max Yavno worked as a Wall Street messenger while attending City College of New York at night. He attended the graduate school of political economics at Columbia University and worked in the Stock Exchange before becoming a social worker in 1935. He did photography for the Works Progress Administration from 1936 to 1942. He was president of the Photo League in 1938 and 1939. Yavno was in the U.S. Army Air Corps from 1942 to 1945, after which he moved to San Francisco and began specializing in urban-landscape photography.

He was one of several post war photographers who lived and worked in what became a new culture, the Southern California middle class leisure car culture.

Roy DeCarava was one of the most influential documentary photographers of the 1950s-1960s. He was known more for the simplicity and ordinariness of his work than for it being spectacular or showy. His particular importance was photographing the Black community of his native Harlem and for the jazz scene of the era.

For a more thorough descrtiption of DeCarava’s work check out the always insightful Claire O’Neil’s essay at: https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2009/10/decarava.html

Abandoned Car in Jamaica Bay 06/1973 by Arthur Tress/Documerica Project

Abandoned Car in Jamaica Bay 06/1973 by Arthur Tress/Documerica Project

For more information on Arthur Tress click here.

Vyacheslav Korotki walks out under a full moon to an abandoned lighthouse

that used to serve the Northern Sea Route, to gather firewood to help heat his home.

Photograph by Evgenia Arbugaeva

Evgenia Arbugaeva was born in the town of Tiksi, located in the Russian Arctic. In 2009, she graduated from the International Center of Photography’s Documentary Photography and Photojournalism program in New York and since then works as a freelance photographer. In her personal work she often looks into her homeland—the Arctic, discovering and capturing the remote worlds and people who inhabit them.

Arbugaeva has been a winner of various competitions. She is a recipient of the ICP Infinity Award, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund Grant. Her work has been exhibited internationally and appeared in such publications as National Geographic, mare, Le Monde, and The New Yorker magazines, among others.

Exurbia #7. Horizon City, Texas, 2018

Text and photograph by Bruce Berman

The Exurbia series concentrates on the landscape that is neither suburban nor urban. It is usually found in the lands just beyond the suburbs, places where individuals and small businesses went, years ago, where the land was cheap and undeveloped. Now The Grid is coming to these places, doing what The Grid does: gobble up the land, erase or sandpaper its textures, oust the one-of-a-kind, make things safe and expected, over-electrified and deadingly dull.

Exurbia is the land that is America today, a place where the suburban cookie cutter machine has come and is bringing the American Dream, which for many is the American Bore.

El Paso, Texas, 2016

Photograph and text by Bruce Berman

This is about “it” folks.

The last of this barrio, this old ‘hood, known in earlier days as El Pujido (the “push” referencing some knife fights the deteriorating barrio came to be known by in the fifties and sixties).

From the west is coming a vicious storm of hipsterism, of micro brewery culture, restaurants with fuzzy foo foo pinched across the top of, well, some tiny thing underneath.

Redoing The Clock. El Paso, Texas, 2018

Redoing The Clock. El Paso, Texas, 2018

It’s been 5:00 o’clock at The Clock on Dyer Street for as long as I’ve been in El Paso (43 years).

It’s reassuring that time does not change particularly after 43 years (if you know what I mean).

But even in a land where time stands still, once in awhile, roadside signs need to be renewed.

It’s an art form. The letters are made of rubbery plastic. You have to know what you’re doing and this phantom sign renewer does. Name? Withheld. Working for the restaurant? Not saying. Getting paid? Maybe.

It’s almost 5:00PM for this image. It’ll be almost 5:00AM in twelve hours.

Even a broken clock is right… twice a day.

Text by Bruce Berman

Whatever this crown was announcing is long gone. A bar? A restaurant? A store? Probably a bar… but who knows?

The photograph of the Crown of Canutillo, Texas is what remains (and perhaps a memory here and there).

Who constructed it? Why a crown in this funky little town that’s on the border up against New Mexico? Was there dancing?

Who knows?

Untitled (2012) from the series Tiksli

by Evgenia Arbugaeva

For more work see: http://bit.ly/2y8bQha

Andreas Feininger, born December 27, 1906, was a pioneer of modern photography. Born in Paris, son of the painter Lyonel Feininger, Andreas was educated in German public schools and at the Weimar Bauhaus. His interest in photography developed while he was studying architecture, and he worked as both architect and photographer in Germany for four years, until political circumstances made it impossible.

West Texas seems vast, seamless, endless and infinite.

But consider the Universe!

No walls. No boundaries?

No end we can even imagine.

Can you get your head around that?

I cannot.

I studied with Ernst, briefly, in 1979. He was a great guy, very honest and one of the most elegant people I ever met. He got excited by Mahler while everyone else was getting excited by the Rolling Stones!

His photography mirrors that elegance. Whether it was for himself or a commercial client (he did a lot of really great stuff for Lufthansa) the work was always personal and usually intriguing.

Enjoy Ernst: http://bit.ly/2BlQZcB

Text by Bruce Berman

Arthur Rothstein was hand picked by Director Roy Stryker to be one of the original photographers for the Historical Section of the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration/FSA). The unit was birthed to be an explainer for agriculture projects that benefited the agrarian sectors of Depression-ravish America. Rothstein’s “eye” was excellent, his technical skills first rate and he always came back with the goods and then some.

Why doesn’t he get the attention of Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans, or, even, Russell Lee?

Was it the cow skull “controversy?”

Perhaps.

For me this “controversy has always seemed,well… overblown. He moved the skull several times and then, finally, settled on the one we all know.

Was he (visually) lying?

I think not.

Migrant Father, June 1938, by Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange’s extended caption:

Old time professional migratory laborer camping on the outskirts of Perryton; Texas at opening of wheat harvest. With his wife and growing family; he has been on the road since marriage; thirteen years ago. Migrations include ranch land in Texas; cotton and wheat in Texas; cotton and timber in New Mexico; peas and potatoes in Idaho; wheat in Colorado; hops and apples in Yakima Valley; Washington; cotton in Arizona. He wants to buy a little place in Idaho

Ice truck, Juarez, 1975

(from Walking Juárez)

This is an image from the upcoming book -Walking Juárez- by Bruce Berman. It is one of the images from the story “Iceman.” It will be available on Amazon (Kindle eBook and Print)and in selected bookstores on July 6, 2017.

Migrant family on highway, California, 1937

Photograph by Dorothea Lange

Extended Caption: California at Last: Example of self-resettlement in California. Oklahoma farm family on highway between Blythe and Indio. Forced by the drought of 1936 to abandon their farm, they set out with their children to drive to California. Picking cotton in Arizona for a day or two at a time gave them enough for food and gas to continue. On this day, they were within a day’s travel of their destination, Bakersfield, California. Their car had broken down en route and was abandoned.

Photo by Leonard Nadel

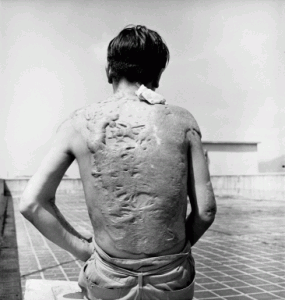

Editor’s Note: The Bracero program addressed the issue of demand for labor and the need for work. It was a cooperative program that allowed America’s work needs to utilize the need of Mexico’s workers’ need for employment. It was legal, it was effective and it was a clear win-win program. Therefore it did not last. Too logical. And here we are now, 52 years later, with America needing workers, Mexicans needing employment and total chaos at the border. One could ask, is this chaos or planned exploitation?

Here is a mini-history of the Bracero Program. Let the discussion begin.

Text by Smithsonian National Museum of American History The Bracero program (1942 through 1964) allowed Mexican nationals to take temporary agricultural work in the United States. Over the program’s 22-year life, more than 4.5 million Mexican nationals were legally contracted for work in the United States (some individuals returned several times on different contracts). Mexican peasants, desperate for cash work, were willing to take jobs at wages scorned by most Americans. The Braceros’ presence had a significant effect on the business of farming and the culture of the United States. The Bracero program fed the circular migration patterns of Mexicans into the U.S.

Several groups concerned over the exploitation of Bracero workers tried to repeal the program. The Fund for the Republic supported Ernesto Galarza’s documentation of the social costs of the Bracero program. Unhappy with the lackluster public response to his report, Strangers in Our Fields, the fund hired magazine photographer Leonard Nadel to produce a glossy picture-story exposé.

Presented here is a selection of Nadel’s photographs of Bracero workers taken in 1956: shttp://s.si.edu/1gRD3VJ for Nadel’s photographs and other resources.

Changing the Tire, Photograph by

Changing the Tire, Photograph by

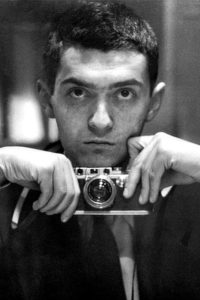

Stanley Kubrick, 1946, for Look Magazine

Not many people think of Stanley Kubrick as a still photographer. After all, the creator of such monumental classics as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. Strangelove and Lolita is etched in our brain as the grand American cinematic auteur.

But, even before all that, he was roaming the streets of New York City, grabbing life as he knew it. He did assignments for major publications of that era, and apprenticed with and later became a staff photographer for LOOK magazine, one of the two giant picture magazine (the other being LIFE).

At LOOK he photographed such greats as Frank Sinatra and Erroll Garner to George Lewis, , Papa Celestin, Alphonse Picou, Muggsy Spanier, Sharkey Bonano, and many of the greatest jazz musicians of the New York scene. It wasn’t until 1948 that Kubrick took an interest in cinema after viewing films at the Museum of Modern Art’s film screenings.

For more on Kubrick: https://twistedsifter.com/2011/12/stanley-kubricks-new-york-photos-1940s/

and: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Kubrick

Tenant farmer moving his household goods to a new farm.

Hamilton County, Tennessee, Rothstein, Arthur, 1937 (LOC)

Ten Children, March 1937, by Dorothea Lange,

for the RA (courtesy of OMCA)

The Funklands are where you find them, and, when.

Bruce Berman started this project when he was in his early 20s, in the 1970s, and just starting out in photography. He cruised the highways and the low-ways of America, no particular agenda, stopping often (to the consternation of those driving with him), always looking for the funk, the detritus of other eras, the iconography of his youth and the times before him.

This America is now almost gone. It hangs over bars in places like Austin or Madison, Los Angeles or Chicago. The Funklands have turned into “Fly Over” territory, still there, still quasi rural, but now, unrobed. The structure of the Funklands, textured, bold, spectacular, has been replaced by franchised plastic, flatness, sameness.

We celebrate corporate identity in the iconography of now, not roosters and skeletons and old Cadillacs.

The Funk has turned from delight to nothingness. Occasionally there is a McDonald’s that riffs on a local theme, but pretty much not.

The Funk is hard to find.

The Pre Art Landscape is one in which there are images only attractive to some’s intellect that titillates the intellect of others who are over educated, over intellectualized, clean from lack of experience with the world that they choose to not touch and where, through their lack of desire to know a world around them other than the one aforementioned, allows them to revere and praise that which is without interest to anyone but them and their ilk.

So here is an image from my Guggenheim Fellowship submission. I created this less than fifteen minutes ago by walking out the back door of my slum loft (yes there are still some around that the yuppies and Julias haven’t occupied and, therefore, chased out those who were living there, not for some feeble concept of what is cool, but because, previously, they could afford the rent if they were willing to put up with the inconveniences and degradations of everything that the word “slum” implies).

If I hadn’t written this piece I very well may have earned a Guggenheim.

I coulda been a contenda…instead of -let’s face it- a bum…which is a what I am…*

I couldn’t resist the rant.

I suspect that’s what has saved my heart’s soul from an early death.

*Thank you Budd Schullberg (http://bit.ly/1KetpPl)

The meteorologists call this a “High Pressure system being pushed out by a Low Pressure system.”

Photographers will admit “every once in a while things come together and you get a lucky.”

What do I call it? What does one get for being out there, every evening and every day, always with your “axe (camera)at the ready, often coming home with nothing but the pleasure of having been out there trying?”

The funny thing is, as usual, I was in a part for town I’d never been in before (there are few left). It is a very unusual ‘hood for El Paso. In another city one would call it the “ghetto.” Here, no one thinks there is a ghetto. Being a predominantly latino city (82%), if you have a neighborhood that is lower income, the natural thing is to call it a barrio. This neighborhood was definitely “low income,” and of the three people I conversed with, two had been drinking alcohol to the point of inebriation. It is a mostly Black neighborhood, unusual in El Paso that is only 4% African-American.

Text by Bruce Berman

All Commentary (definitely) Subjective

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) started out to show government programs to the taxpaying public, to gain support for the New Deal agriculture initiatives of the Resettlement Administration (RA). From mid 1936 to late 1939 it did that but in the doing it found itself -pushed by the hand of its Director, Roy Stryker- documenting “American Life.”

The beginning of the FSA concentrated on the devastation of people and land of the agrarian sector but, as time went on, it broadened its image-making to include the way all Americans lived and worked.

The America of the 1930s is still out there, in the backlands, far away from the eyes of urban America. In fact, if one only learned of the interior of America from the mainstream media (all situated in urban America) one could not know that the America of the 1930s FSA is ongoing, alive, and functioning.

These images are a sample from the FSA road, a road I travel often, now, in 2015, seventy nine years after the creation of the FSA and their portrayal of America.

Then as now it is typified by open space, graphic simplicity and, agriculture and a sense of order now uncommon in urban America.

Text and photograph by Bruce Berman

El Paso is in transition. It was always complicated. There was the whole “Southwest” thing and then again, there was the whole Chicanismo thing, and then again there was the cowboy thing, and then again there was a certain ex Pat vibe for 60s and 70s refugees who never went home.

And there was the growing suburban thing, the Ohio is too cold and El Paso is affordable tilt.

Viva complication!

Now El Paso is getting more simple. It is trying to spruce itself up and become a destination. They have a baseball team downtown now, and a restored fancy movie theater within walking distance of it and there are bicycle riders and bicycle lanes everywhere ( a sure sign that the “texture days” are done).

It’s still El Paso but some (real estate developers and those that are young that can’t quite make it out) hunger for it to be Cincinnati. Good luck.

For those who have known El Paso for many decades, to see court jester-dressed bicyclists pedaling through downtown is jarring. It is a pure contrast to the bruised authenticity that has been El Paso’s greatest strength (for me), for those of us who have been hiding here.

Kimball the American, El Paso, Texas, by Bruce Berman

Commentary by Bruce Berman, Editor

Why is it the street guys not only aren’t shy about flying “Old Glory,” but are vigorous in telling you why they love it? Compare this to any college campus. Not only can you not find a glimpse of the Stars and Stripes, there are numerous organizations that want it -or anything it represents….like the military- anywhere near it.

Is a puzzlement or is it an insight?

Perhaps, as we look at the condition of the country and the rumors of its demise, we need to start looking to the streets for some answers, not to the walls of academe.

Viva Kimball.

Editor’s note: Susan Meiselas, Magnum Photographer and long time great documentarian, discusses documentary photography, motivations, uses, intentions and hopes for the work’s impact on subjects and society.

This project, funded by the Open Society Foundations (Meiselas Co-Curated the project’s exhibition), shows the work of some of the world’s best contemporary photographers working in this discipline.

Bridesmaids and best man at a wedding in Chavez Ravine, 1929.

Courtesy of the Shades of L.A. Collection, Los Angeles Public Library

Louie Schwartzberg speaks at the TED lecture.

This is a beautiful piece and should change your (and everyone’s) life:

Restoration Square, Lisbon, Portugal. Photo: Horácio Novais Studio

A beautiful set of photos of Portugal at night, through the years, shot on Portugal Day.

Officially observed only in Portugal, Portuguese citizens and emigrants throughout the world celebrate this holiday. The date commemorates the death of national literary icon Luís de Camões on 10 June 1580.

Our colorful universe or good Acid trip?

Photo: NASA

From OMG Facts

Source: http://hubblesite.org/gallery/behind_the_pictures/meaning_of_color/

NASA says that taking color pictures with the Hubble telescope is much more complex than taking pictures with a regular camera. The reason for this is that the telescope uses special electronic detectors instead of using film.

The finished pictures that we see are actually combinations of various black-and-white exposures to which color has been added. Sadly, this means that sometimes they play with color as a tool. The colors you see on a photo aren’t necessarily what you’d see in real life.

The way they do it, is they have different filters that capture different sections of the color spectrum. For example, they will adjust their sensors to capture red light, then green light, then blue light.

This gets them 3 black and white photos. However, they each are of a different brightness depending on what color it is. In a picture of Mars, the red photo will be brighter than the others.

After they color each photo, they combine them and the result is the photos you see them publish!

Article edited and written by Bruce Berman

Carl Mydans began his photographic career with the Farm Security Administration in 1935, and was quickly hired away by Life magazine in 1936. Mydans photographed national stories until 1939, when Life sent Carl and his wife Shelley Smith Mydans to cover the war in Europe as the first husband and wife photo-journalist team.

From Europe, the couple was re-assigned to the Pacific theater. In 1941 they were captured by Japanese forces in the Philippines and held as prisoners of war until 1943. Mydans returned to the war alone in 1944 to cover the Italian front, while his wife and partner remained behind in the United States.

Carl Mydans was born in Boston on May 20, 1907. The family moved to Medford, Massachusetts, on the Mystic River where Carl went to high school and worked in the local boatyards after school and on weekends. He later became interested in journalism and worked as a free-lance reporter for several local newspapers. In 1930 he graduated from the Boston University School of Journalism.

Mydans then moved to New York and, while working as a reporter for the “American Banker,” began to study photography at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. In July 1935 his skill with the new 35mm “miniature” camera landed him a job with the Department of the Interior’s Resettlement Administration, which soon merged into the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Mydans joined Walker Evans and Arthur Rothstein as the core of the remarkable team of photographers assembled by Roy Stryker to document rural America.

While travelling through the southern states photographing everything that had to do with cotton, Mydans developed the shooting style he would use throughout his career. He concentrated on people, and he photographed them in a respectful and straightforward manner. As he had been taught to do as a reporter, he kept careful notes on every shot.

When Mydans joined the staff of Life in 1936 he joined a group of photojournalists who were changing the way press photography was done. Photojournalists had traditionally used 4×5 Speed Graphic cameras with flashguns and reflector pans, and their pictures of people tended to look much the same: overlit foregrounds fell off to dark backdrops that had no detail. But Mydans and his colleagues at Life relied on 35mm cameras that allowed them to work with available light, capturing a new kind of excitement and activity in their photographs. Their success with the small camera revolutionized the practice of photojournalism.

Images from NIGHT TREK series. I take strolls. I shot whatever I see. Like the old days before I was supposed to “be relevant.” The phonier is dumb, There’s always fingerprints (which one forgets to wipe off) because it’s in my pocket with change, keys, debris. I’m not caring because the point isn’t to be a photographer but to stroll. I think Cartier-Bresson said something about a photographer needs to be a good “stroller.”

I’m a good stroller anyway.

All these were shot on the mobile phone camera three days ago, Monday, May 21, in the Segundo barrio, the place that I stroll often and for years.

The quality of the “tech” is marginal.

Admittedly.

BUT, the liberation of just being another idiot with a cell phone, priceless!

The mobile phone returns one (especially one who no longer looks like a Spring Chicken) to the roots, invisibility, just another vato in the ‘hood. I hate bad technique, but, I love being FOW again (fly on the wall).

What do you think? Lower technique but higher involvement? Or go for higher technique and be the outsider jamming that thing into people’s lives?

Are Phonera’s a democratizing Good Thing?

You got to love paper. And aging. And photos. And writing.

Yes, it’s all in the “database” there, at the end of the keyboard, through Google. But is it?

Even if it is it has no texture, no odor, no reality.

Take this trip to The New York Times Morgue. A perfectly wonderful place to spend a lifetime.

Here is a nice vision for a documentary project that involves multiple photographers, blending old and new.

If you speak Chinese you can forgo the subtitles!

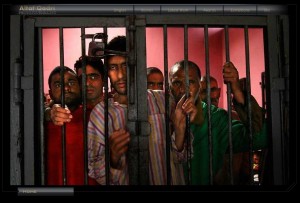

Altaf Qadri, 35, is an award winning photographer.

Qadri, 35, won a World Press Photo award this year for his poignant photograph of relatives mourning over the body of a man killed in a shooting by Indian police in Indian-controlled Kashmir.

photography Altaf Qadri

Qadri, an Indian citizen, is a native of the Kashmiri city of Srinagar. He studied science at Kashmir University and worked as a computer engineer before taking a job as a staff photographer at a local Kashmiri newspaper in 2001.

CLICK ON THIS IMAGE FOR MORE Altaf Qadri:

In 2003, he joined the European Press Photo Agency and covered the conflict in Kashmir. In 2008, he began working for The Associated Press in the Indian city of Amritsar. His work has appeared in magazines and newspapers around the world and has been exhibited in the United States, China, France and India.

From Shantytown by André Cypriano-©2011

From Shantytown by André Cypriano-©2011

André Cypriano takes us into the forbidden hills of Caracas Venezuela. He takes us into a strange land of oddly shaped houses, winding streets carved out of the hills, into a land so odd and so foreign that it must be myth but can only be reality. He notices, as all greart documnentarey phtography does, that ordinary reality, in some cases, is always more intense and mind-boggling than any fiction can be,

Cypriano takes us to Rochinha.

How he got there, who gave him access and what he encounters is worth serious viewing time. In the New York times Lens Blog post, below, wander with André.

He will take you on a journey you well not forget.

For more from André Cypriano, see:

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/06/in-brazil-finding-dignity-in-horror/

[flagallery gid=1 name=”Gallery”]

El Paso —-

Bruce shoots Juárez. Reluctantly and with remorse.

Since 2008 the photographer has been documenting the aftermath of violence in the troubled northern Mexico city. His interest is in the effect of the Cartel War on the population of the city, particularly the effect on the children of the city who have grown up knowing little else.

His current work is in a mental institution in the city, what he refers to as “The House Of The Abandoned.”.

The body of work -The Other Truth- will appear on this site on November 18th.

Hungary Baths by Amy Vitale©2011

From Ami Vitale’s website (http://www.amivitale.com):

Ami Vitale’s journey as a photojournalist has taken her to more than 75 countries. She has witnessed civil unrest, poverty, destruction of life, and unspeakable violence. But she has also experienced surreal beauty and the enduring power of the human spirit, and she is committed to highlighting the surprising and subtle similarities between cultures. Her photographs have been

exhibited around the world in museums and galleries and published in international magazines including National Geographic, Adventure, Geo, Newsweek, Time, Smithsonian. Her work has garnered multiple awards from prestigious organizations including World Press Photos, the Lowell Thomas Award for Travel Journalism, Lucie awards, the Daniel Pearl Award for Outstanding Reporting, and the Magazine Photographer of the Year award, among many others.

Now based in Montana, Vitale is a contract photographer with National Geographic magazine and frequently gives workshops throughout the Americas, Europe and Asia. She is also making a documentary film on migration in Bangladesh and writing a book about the stories behind the images.

Article posted courtesy of Huffington Post and Steve Ettlinger

Is Photojournalism Dead Yet?

by Steve Ettlinger

Born in the 1930?s, come of age in the 1950?s and 60?s, and pronounced near dead in the 1970?s and virtually buried by the closing of magazines/rise of the internet–you have to wonder how it is that some aspects of this wonderful world are still around.

Editor’s Note: This is an amazing project. In the era when people worry about the demise and/or future of journalism, when academics question the effectiveness of journalism in a 24/7 news cycle world, there is JR, who is producing and promoting another form of photojournalism and not only bringing his subjects into the communication process, he is bringing the work done on the subjects back to their environments. Check it out:

INSIDE OUT is a large-?scale participatory art project that transforms messages of personal identity into pieces of artistic work. Everyone is challenged to use black and white photographic portraits to discover, reveal and share the untold stories and images of people around the world.

SEE VIDEO

Andrea Bruce is a passionate, stylish, skilled documentary photography who’s images -in the best traditions of still photography- sear your soul and drive their point through your heart, restoring it instead of terminating it. She is the new breed of documentary photographer that blends all the skills of good journalism with all the skills of great graphic image-making and produces a coctail that is nothing less than photo alchemy.

Take a look: http://www.andreabruce.com

Contact Sheet of Ashley Gilbertson’s Conflict Photography

“He has a very good news sense and for me that’s really essential,”

says Cecilia Bohan, foreign picture editor for The New York Times.

“I need them [her photographers] to be my eyes and ears on the ground.”

Ashley Gilbertson is a VII photographer and one of the strongest Conflict Photographers working today. His recent work, done far from the battlefield but in the bedrooms of fallen soldiers, is one of the strongest testaments to the outright sadness about Loss that War induces, that this editor has ever seen.

For a sample of Mr. Gilbertson’s work:

These are not the view of Japan that we normally see. Shiho Fukada shows us how some elderly people in Japan fare. It is not a story unique to Japan.

SEE http://www.socialdocumentary.net/exhibit/shiho_fukada/728

[pro-player width=’600′ height=’500′ type=’video’]https://documentaryshooters.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/PearlOnFilm3.mov[/pro-player]

Lost Boys of Afghanistan by Moises Saman

See this stirring slideshow by Moises Saman shot for The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2009/08/27/world/20090827AFGHANMINORS_index.html

Self portrait by Evegen Bavcar

Photography has always been thought about as “another,” way of seeing.

And it is.

But, usually, we think about that as a person looking through the camera, seeing what’s there, and, through the magic of the camera and the film -or digital- capture process, one sees the world in different way.

More advanced photographers and appreciators of photography then allow for the transformative recognition of the quality and angle of light, of the Decisive Moment, of the power of distance to subject or, even, luck or magic.

It is this latter idea that infuses the work of Evgen Bavcar ((“E-oo-gen Ba-oo-char”), the Slovenian photographer is completely blind, completely eccentric and his images are totally wonderful.

[pro-player]https://documentaryshooters.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/my-name-is-dechen.flv[/pro-player]

“My name is Dechen.”

Watch this touching video done by Dhiraj Singh.

He did an interesting thing: A Video Biograph.

In a way, all Visual Journalists who do stories on people, are doing “biography,” but with the addition of audio, where the subject can speak for themselves (edited, of course), where the image-maker can animate the images and drive the viewer’s emotions, the subject of the story becomes more “alive,” the depth is ratcheted up, and, potentially, the medium is beginning to resolve the age old struggle of photojournalism: Who’s viewpoint is this about? The subject’s or the photographer’s?

From “Six Feet Under,” ©2009Dhiraj Singh

For more work by Dhiraj Singh, SEE: http://www.dhirajsingh.com/01.htm

Dhiraj Singh is a Photojournalist who lives in Mumbai, India. His work has been published in numerous international magazines and online journals, including Newsweek, Vanity Fair, msnbc.com, The Wall Street Journal, L’Expresso, and, many others. He has won numerous awards (see his “bio,” on his site, above) and participated in many exhibitions. His pictures of the Mumbai terror attacks in 2008 were part of the prestigious group exhibition titled, ‘Bearing Witness’ held in Mumbai in 2009.

Documentaryshooters is honored to have permission to publish Mr. Singh’s work. We feel he has the insights and skills to show India as it is, depicting its greatness and its struggles, its deep and ancient soul as well as its modern and energetic heart. He, as no other photographer has, since, the great Raghu Rai’s seminal work of the 1970’s, ’80’s and 90’s, not only shows India and the sub continent, he makes us feel it.

Parikrama: But It Rained from Split Magazine on Vimeo.

This is a rock band video based on a magazine article about kidnap victims in Kashmir and those who wait for their return. This is one of India’s most revered bands and was one of India’s all time most popular rock songs.

Sometimes we forget that the “Big Work,” the work that one becomes known for making isn’t all there is.

Bruce Davidson went south, from Chicago, on instinct.

The world was shaking and he felt the vibe.

The time was now: Civil Rights.

Real change.

Without assignment or specific destination he “nailed it,” and was able to work on the edges of the news, tell the story from a personal and deeply intimate viewpoint.

This image, for me, is one his best. Beautiful composition. Beatiful moment. Beautiful storyline. Iconic and packed with all the elements that make it a novel unto itself, if this was the only photography that existed from the era it was shot in, it would, I think, be enough to tell the story of the struggle.

One word and one image: sometimes it’s enough: Vote.

For More on Bruce Davidson: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce_Davidson_(photographer)

Man selling popcorn at a moulid, Tanta, Egypt, ©Shawn Baldwin

GO TO: http://www.shawnbaldwin.com/

Shawn Baldwin’s photographs of Egypt are lyrical, soft, sometimes tough, nuanced and, mostly, an eye that sees with the heart and feels with the intellect.

This is the kind of documentary that lets its viewers see as if they were there (although you’d have to be looking as hard as he is and putting in your time to get these beautifully done images).

In the end, because these are not screaming and specific, this work let’s us know a place and people without prejudice.

GO TO: http://todayspictures.slate.com/20090610

It can’t all be angst and drum!

Every once in awhile a good shooter has got to have some fun, or, at least, see others having fun.

That’s worth a document, right?

People still having fun?

Concept!

©2009 Photograph by Mimi Chakarova

GO TO: http://www.mclight.com/slideshow.html

Editor’s Note

This is one of the most painful documentaries I have ever seen.

Even more amazing is the fact that the work is not the slam and splash type of photojournalism that deals in blood, guts and flames.

©Victor Sera

GO TO: http://www.fiftycrows.org/index.php#mi=2&pt=1&pi=10000&s=1&a=7&p=0&at=3

This is a photo essay on the lives of the undocumented as they navigate between their homes and their country chosen for work.

In some ways the “landscape,” of this document has changed since it was photographed in the 1990’s. The immigration interdiction efforts by the United States has reduced the number of migrants and, more recently, the lack of jobs in the U.S. due to the faltering economy has reduced it even further. The personal plight for migrants in the U.S. has changed for the worse, making any return to the mother country impossible due to the danger of the return journey.

This document, however, is still quite valid. The existential delemna of home and heart weighed against stomach and uprootedness is ongoing, worldwide and, as this work shows, problematic.

©Olivier Jobard

GO TO: http://mediastorm.org/0010.htm

This is an uplifting story of “one man’s willingness to abandon everything – his family, his country, and his friends – in the hopes of finding a better life abroad.”

This Mediastorm produced slide show of Olivier Jobard’s masterful photo essay, follows Kingsley from his home in Cameroon, through Africa and, eventually ending in the land of the “Holt Grail,” Europe.

The journey is not without its dangers and indignities for Kingsley, but another amamzing journey is Jobard’s herself.

East Side Stories/© Joseph Rodriquez

SEE: http://www.josephrodriguezphotography.com/index.php#a=0&at=0&mi=2&pt=1&pi=10000&s=0&p=5

Rodriquez goes where everyone else tries to stay away from: East LA.

This is a strong documentary of the gangs of East LA that goes beyond the dramatic into the intimacy of humans who live in a situation.

SEE: http://www.american-pictures.com/gallery/index.html

Note: Jacob Holdt’s photographs of hate and racism demonstrate the fact that the emphasis in documentary photography is on the word documentary. Sometimes Holdt’s images are a little soft focused or grainy or whatever else one considers technically “flawed(as were Hine’s, Riis’s and every other documentary photographer who was/is worth anything) ,” but, never does his work not deliver the goods: truth simply spoken.

Holdt used this camera

[ http://www.camerapedia.org/wiki/Canon_Dial_35 ]

to record over 20,000 images of “hate, racism and “white hate groups.”

He does not consider himself to be a “photographer,” but, rather, an observer, a participator, a witness. Check his site out. It is an incredibly disturbing -and eye opening- view of America. To my mind, Holdt presents a more thorough document than the two year event of Robert Frank and his Guggenheim sponsored “Americans.”

Here is presented Holdt’s Opus: a fairly unknown collection of his massive look at America’s underbelly.

Jacob Holdt’s Vagabond yearsArriving in America with only $40 for a short visit, a young Dane, Jacob Holdt ended up staying over five years, hitchhiking more than 100,000 miles throughout the USA.

SEE: http://www.nbpictures.com/site_home/movie.php

SEE: http://www.nbpictures.com/site_home/movie.php

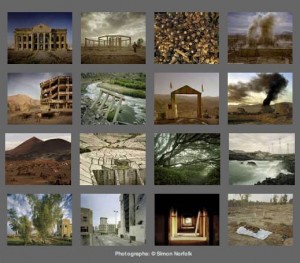

GO TO: Menu>Portfolio>Simon Norfolk>Portfolios

This is an arresting and strangely beautiful look at the eerie landscape left by war.

Norfolk, a trained photojournalist, turned away from the live action kind of document and approached the look of war by pointing himself at the aftermath of war as it manifests itself on the landscape. His work from Afghanistan and Iraq tells another story of war and, like all war photography is a combination of destruction, unbelievable moment and twisted beauty.

SEE: http://www.nbpictures.com/site_home/movie.php

SEE: http://www.nbpictures.com/site_home/movie.php

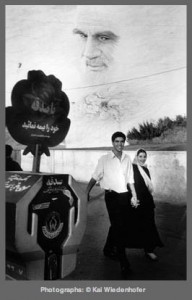

GO TO: MENU>FEATURES>CURRENT AFFAIRS>IRAN’S YOUTH

This photo essay is of the youth of Iran. Kai Weidenhofer, who is a Middle East specialist gets to the truth of the matter: it’s a small planet, so what’s the big deal?

SEE: http://mediastorm.org/0024.htm

Here is a quintessential insight into the drive to do documentary photography, a chilling portrayal of the challenges of working within difficult environments and of turning horror into hope. Listen to Jonathan Torgovnik talk about rape, murder and redemption in Rawanda.

Moody, not edgy.

Sincere.

Image maker.

In his words, “It’s kind of hard to put into words what I do.”

SEE: http://mediastorm.org/0023.htm

A documentary project on Displacement…in the “Heartland!

This photographer shows how “progress,” comes to everywhere and the displacement is not limited to indigenous people either. In the end it is the interests of Capital weighed against the interests of Labor that is the issue of land appropriation and displacement.

Let this documentary speak for itself.

The great Brazilian photographer Sabastio Salgado talks about his work and his career: