Been crazy about tires from the beginning!

Still am.

Why?

No idea.

Fix Flats, Clint, Texas, 2024, photograph by James Yontrofsky

Been crazy about tires from the beginning!

Still am.

Why?

No idea.

Fix Flats, Clint, Texas, 2024, photograph by James Yontrofsky

Baterias Luchador, El Paso, Texas, October 2022

Things stick with you.

Forever.

Particularly bad things.

No amount of money can undo things you did that you shouldn’t have.

Maybe in heaven…

Kozelek’s always been eclectic (and superb).

This one is particularly touching.

William Klein is an American-born French photographer (b. 1928) and filmmaker noted for his ironic approach to both media and his extensive use of unusual photographic techniques in the context of photojournalism and fashion photography. He used telephoto lenses to shoot fashion before it became standard, he cranked his enlarger’s focusing knob back and forth to create a weird zoom look, he shot high fashion on the streets without permits and, most of all he always stayed rebellious, innovative and, well… different.

He has lived in Paris since the 1960s and is still creating new work which is widely exhibited.

Klein was a pioneer not only in fashion photography but in independent filmmaking and street photography and now, in his fusion of painting and photography.

For an excellent insight into the great Klein, view the full length (58:43) video below. For a gallery of his still photography check out the link to the right under Great Photographers.

Text by Bruce Berman

Photograph by Stephen Wilkes

My father, Irving “Punch” Berman was born on Ellis Island in 1906. It was the day his parents -my grandparents- arrived in America. He was the first American in our family.

He was grateful to be here.

The documentation of “The Island” by Stephen Wilkes is documentary photography at its best: it preserves our memories and it stimulates inquiry.

See Stephen’s work: https://stephenwilkes.com/fine-art/ellis-island/

Was this the exact room he was born in? Who knows?

Was this the exact clinic? Yes.

Was he an accidental American? Most definitely.

The mystery in our family was, always, twofold: a) why did they let them in? My grandfather, Jacob, was dead within 6 months, of Tuberculosis. He never made it out of the lower east side. He was that sick it must have shown as the entry guards were interviewing. His mother, my grandmother Anna, died of the same illness seven years later (in Denver). The immigration authorities usually sent the sick ones back on the boat as it turned around and went back to England or Lisbon or wherever. It normally would have been a long sail back to Odessa (which they were escaping from, from the Cossacks), or wherever they could afford to be. And, c) When did he become a Berman. For that matter when did he become Irving? I know how he became Punch because he told me so. That will have to wait for another post (tease tease).

My niece Isabel, has tracked down the family history and it turns out his name was Isidor Yonofsky.

Some secrets, I guess, are lost to the fogs of time.

Note: Much thanks Stephen Wilkes.

Abandoned Car in Jamaica Bay 06/1973 by Arthur Tress/Documerica Project

Abandoned Car in Jamaica Bay 06/1973 by Arthur Tress/Documerica Project

For more information on Arthur Tress click here.

Carole Warrington and her Menominees. Chicago, 1970 by Bruce Berman

On May 5, 1970, a group of American Indians set up an encampment behind Wrigley Field. Led by Indian activist Mike Chosa, and Menominee Carol Warrington, the Chicago Indian Village (CIV) protested against inadequate housing and social services for Chicago’s 15,000 American Indians. The occupation of Wrigley Field’s parking lot began with CIV’s when a Ms. Warrington was evicted from her Wrigleyville apartment (she refused to pay the rent claiming the apartment was substandard and that the City Housing Authority was not inspecting it and forcing slum landlords to bring it up to code). This eviction led the group to a two-month encampment at a Wrigley Field parking lot.The following summer, Chosa and Worthington led a group of fifty men, women, and children in a two-week occupation of an abandoned parcel of government land, a former Nike missile base, at Belmont Harbor. Evicted from the site, they took refuge at the Fourth Presbyterian Church.

This action was part the American Indian Movement (AIM), which is still active and is an activist group that fights for Native American rights.

Exurbia #7. Horizon City, Texas, 2018

Text and photograph by Bruce Berman

The Exurbia series concentrates on the landscape that is neither suburban nor urban. It is usually found in the lands just beyond the suburbs, places where individuals and small businesses went, years ago, where the land was cheap and undeveloped. Now The Grid is coming to these places, doing what The Grid does: gobble up the land, erase or sandpaper its textures, oust the one-of-a-kind, make things safe and expected, over-electrified and deadingly dull.

Exurbia is the land that is America today, a place where the suburban cookie cutter machine has come and is bringing the American Dream, which for many is the American Bore.

Roger Minnick is the voice and the heart of Southern California, especially in the 1970s and 80s. This was the California that the rest of the USA flocked to. Surfin’ USA!

Minnick always has had his finger on the pulse of the state. He just “gets it.”

For more work by the incredible Minnick, see: https://www.rogerminick.com/southland

Andreas Feininger, born December 27, 1906, was a pioneer of modern photography. Born in Paris, son of the painter Lyonel Feininger, Andreas was educated in German public schools and at the Weimar Bauhaus. His interest in photography developed while he was studying architecture, and he worked as both architect and photographer in Germany for four years, until political circumstances made it impossible.

I studied with Ernst, briefly, in 1979. He was a great guy, very honest and one of the most elegant people I ever met. He got excited by Mahler while everyone else was getting excited by the Rolling Stones!

His photography mirrors that elegance. Whether it was for himself or a commercial client (he did a lot of really great stuff for Lufthansa) the work was always personal and usually intriguing.

Enjoy Ernst: http://bit.ly/2BlQZcB

Text by Bruce Berman

Arthur Rothstein was hand picked by Director Roy Stryker to be one of the original photographers for the Historical Section of the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration/FSA). The unit was birthed to be an explainer for agriculture projects that benefited the agrarian sectors of Depression-ravish America. Rothstein’s “eye” was excellent, his technical skills first rate and he always came back with the goods and then some.

Why doesn’t he get the attention of Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans, or, even, Russell Lee?

Was it the cow skull “controversy?”

Perhaps.

For me this “controversy has always seemed,well… overblown. He moved the skull several times and then, finally, settled on the one we all know.

Was he (visually) lying?

I think not.

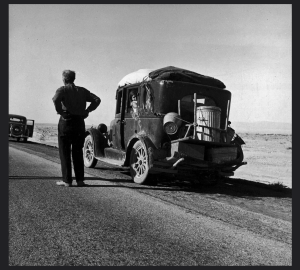

Migrant family on highway, California, 1937

Photograph by Dorothea Lange

Extended Caption: California at Last: Example of self-resettlement in California. Oklahoma farm family on highway between Blythe and Indio. Forced by the drought of 1936 to abandon their farm, they set out with their children to drive to California. Picking cotton in Arizona for a day or two at a time gave them enough for food and gas to continue. On this day, they were within a day’s travel of their destination, Bakersfield, California. Their car had broken down en route and was abandoned.

The DOCUMERICA project was created in 1972 and its Director, Gifford Hampshire, tried to recreate the all-encompassing visual story of America that Roy Stryker began in 1936 with the Farm Security Administration project that told the story of the Depression and, more generally, the story of America as it struggled through the Depression and then toward the end in 1939, told the story of a strong America, preparing for war.

Charles O’Rear was one of the notable photographers for DOCUMERICA. For more about him, including the story of how he created Bliss (the iconic Microsoft screen image) view: https://youtu.be/_G5Z8aMctBw

Photo by Leonard Nadel

Editor’s Note: The Bracero program addressed the issue of demand for labor and the need for work. It was a cooperative program that allowed America’s work needs to utilize the need of Mexico’s workers’ need for employment. It was legal, it was effective and it was a clear win-win program. Therefore it did not last. Too logical. And here we are now, 52 years later, with America needing workers, Mexicans needing employment and total chaos at the border. One could ask, is this chaos or planned exploitation?

Here is a mini-history of the Bracero Program. Let the discussion begin.

Text by Smithsonian National Museum of American History The Bracero program (1942 through 1964) allowed Mexican nationals to take temporary agricultural work in the United States. Over the program’s 22-year life, more than 4.5 million Mexican nationals were legally contracted for work in the United States (some individuals returned several times on different contracts). Mexican peasants, desperate for cash work, were willing to take jobs at wages scorned by most Americans. The Braceros’ presence had a significant effect on the business of farming and the culture of the United States. The Bracero program fed the circular migration patterns of Mexicans into the U.S.

Several groups concerned over the exploitation of Bracero workers tried to repeal the program. The Fund for the Republic supported Ernesto Galarza’s documentation of the social costs of the Bracero program. Unhappy with the lackluster public response to his report, Strangers in Our Fields, the fund hired magazine photographer Leonard Nadel to produce a glossy picture-story exposé.

Presented here is a selection of Nadel’s photographs of Bracero workers taken in 1956: shttp://s.si.edu/1gRD3VJ for Nadel’s photographs and other resources.

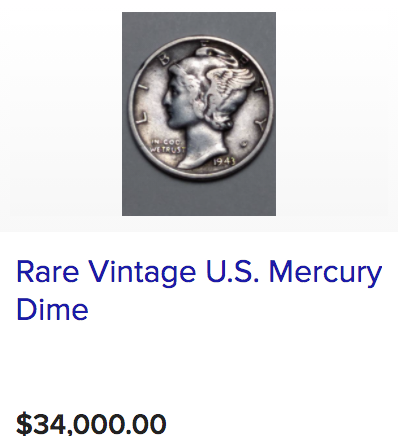

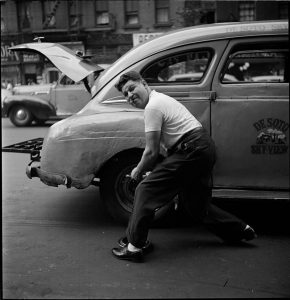

Changing the Tire, Photograph by

Changing the Tire, Photograph by

Stanley Kubrick, 1946, for Look Magazine

Not many people think of Stanley Kubrick as a still photographer. After all, the creator of such monumental classics as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. Strangelove and Lolita is etched in our brain as the grand American cinematic auteur.

But, even before all that, he was roaming the streets of New York City, grabbing life as he knew it. He did assignments for major publications of that era, and apprenticed with and later became a staff photographer for LOOK magazine, one of the two giant picture magazine (the other being LIFE).

At LOOK he photographed such greats as Frank Sinatra and Erroll Garner to George Lewis, , Papa Celestin, Alphonse Picou, Muggsy Spanier, Sharkey Bonano, and many of the greatest jazz musicians of the New York scene. It wasn’t until 1948 that Kubrick took an interest in cinema after viewing films at the Museum of Modern Art’s film screenings.

For more on Kubrick: https://twistedsifter.com/2011/12/stanley-kubricks-new-york-photos-1940s/

and: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Kubrick

Tenant farmer moving his household goods to a new farm.

Hamilton County, Tennessee, Rothstein, Arthur, 1937 (LOC)

Ten Children, March 1937, by Dorothea Lange,

for the RA (courtesy of OMCA)

The Funklands are where you find them, and, when.

Bruce Berman started this project when he was in his early 20s, in the 1970s, and just starting out in photography. He cruised the highways and the low-ways of America, no particular agenda, stopping often (to the consternation of those driving with him), always looking for the funk, the detritus of other eras, the iconography of his youth and the times before him.

This America is now almost gone. It hangs over bars in places like Austin or Madison, Los Angeles or Chicago. The Funklands have turned into “Fly Over” territory, still there, still quasi rural, but now, unrobed. The structure of the Funklands, textured, bold, spectacular, has been replaced by franchised plastic, flatness, sameness.

We celebrate corporate identity in the iconography of now, not roosters and skeletons and old Cadillacs.

The Funk has turned from delight to nothingness. Occasionally there is a McDonald’s that riffs on a local theme, but pretty much not.

The Funk is hard to find.

The meteorologists call this a “High Pressure system being pushed out by a Low Pressure system.”

Photographers will admit “every once in a while things come together and you get a lucky.”

What do I call it? What does one get for being out there, every evening and every day, always with your “axe (camera)at the ready, often coming home with nothing but the pleasure of having been out there trying?”

The funny thing is, as usual, I was in a part for town I’d never been in before (there are few left). It is a very unusual ‘hood for El Paso. In another city one would call it the “ghetto.” Here, no one thinks there is a ghetto. Being a predominantly latino city (82%), if you have a neighborhood that is lower income, the natural thing is to call it a barrio. This neighborhood was definitely “low income,” and of the three people I conversed with, two had been drinking alcohol to the point of inebriation. It is a mostly Black neighborhood, unusual in El Paso that is only 4% African-American.

Text by Bruce Berman

All Commentary (definitely) Subjective

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) started out to show government programs to the taxpaying public, to gain support for the New Deal agriculture initiatives of the Resettlement Administration (RA). From mid 1936 to late 1939 it did that but in the doing it found itself -pushed by the hand of its Director, Roy Stryker- documenting “American Life.”

The beginning of the FSA concentrated on the devastation of people and land of the agrarian sector but, as time went on, it broadened its image-making to include the way all Americans lived and worked.

The America of the 1930s is still out there, in the backlands, far away from the eyes of urban America. In fact, if one only learned of the interior of America from the mainstream media (all situated in urban America) one could not know that the America of the 1930s FSA is ongoing, alive, and functioning.

These images are a sample from the FSA road, a road I travel often, now, in 2015, seventy nine years after the creation of the FSA and their portrayal of America.

Then as now it is typified by open space, graphic simplicity and, agriculture and a sense of order now uncommon in urban America.